Is the Early 21st Century of 'Blade Runner' (1982) Better Than the One We Got?

Even a famously 'dystopian' sci-fi film seems better than our Woke present.

Blade Runner (1982) is one of my all time favourite films. The story and themes of the film are of course fantastic, however, the story is not what I’m going to be talking about, as good as it is. I am instead going to be focusing on the setting.

The original 1982 Blade Runner was set in Los Angeles in a fictional ‘2019’. As that year is now in the past, I want to ask the question of whether the alternate Los Angeles of 2019 is better than the one we got?

Of course, it all depends on your personal values. To the Woke left, the world of Blade Runner would naturally be dystopian. It is hypercommercialist, expansionist, and anti-egalitarian. Ethno-nationalists would also dislike it because it shows a future of mass immigration and ‘White flight’.

But compared to our current world of mandatory DEI seminars, constant promotion of White male guilt, and the mutilation of children being celebrated as ‘trans liberation’, the spectre of a society utterly opposed to all of these values sounds very nice to me.

In this article I’m going to be exploring the society of Blade Runner. I will refer to the setting of the film as ATL (alternate timeline) Los Angeles, and refer to the present as OTL (original timeline), as the film can now accurately be described as a work of alternate history.

What Makes the Aesthetics of Blade Runner so Compelling?

Video: Deckard meets Rachel scene.

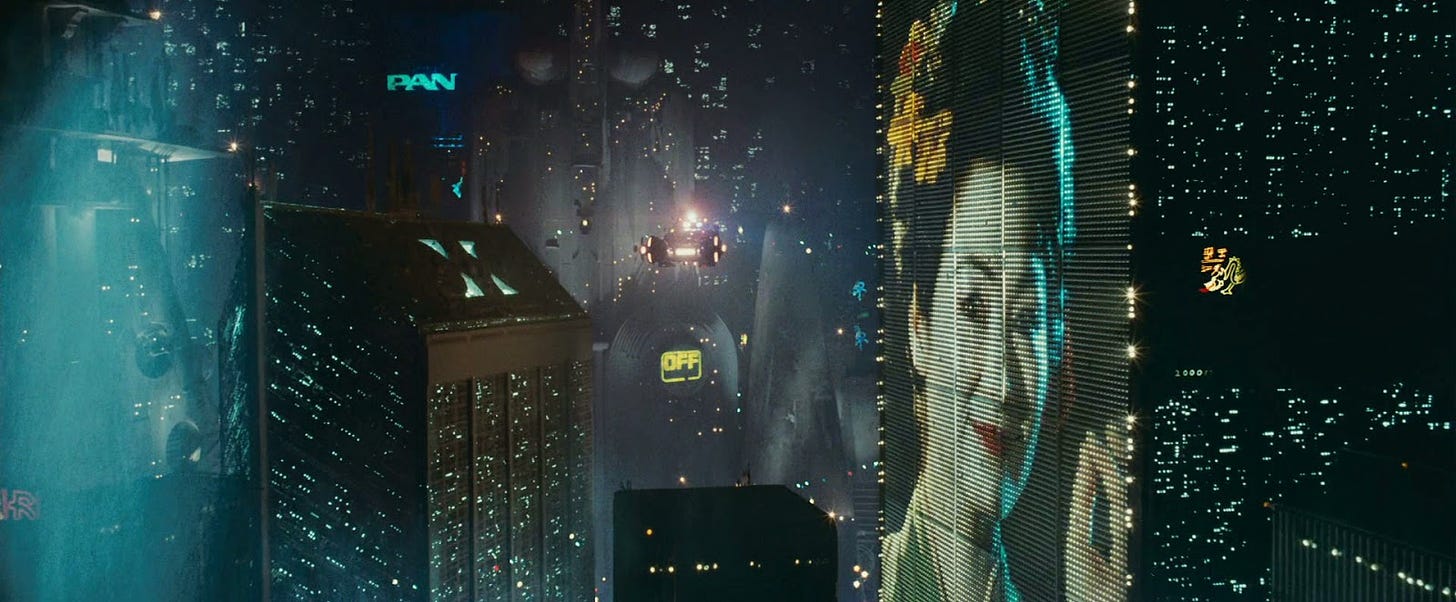

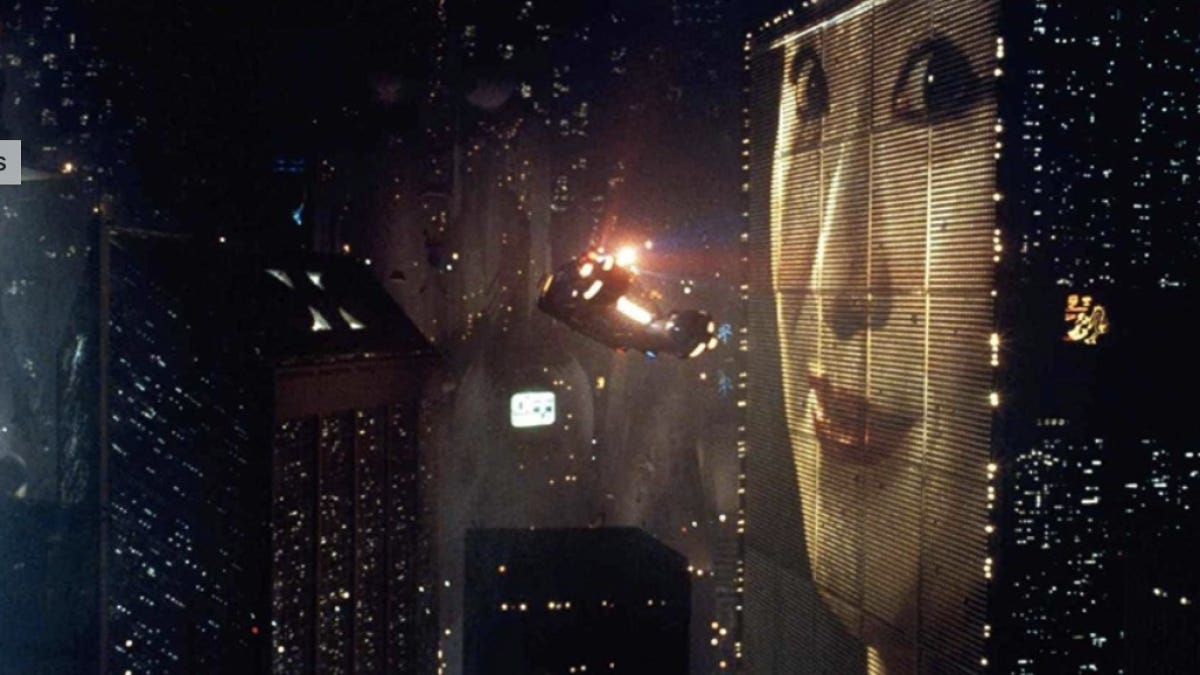

Blade Runner’s aesthetics are beautiful. The electronic score by Vangelis gives a sense of otherworldliness and techno-mysticism that make the world presented in the film seem far more futuristic than today, despite far more primitive computer interfaces.

Indeed, as an older Zoomer, the film’s score reminds me of the soundscape of Windows XP, with some of my earliest memories being me using that operating system.

With it, comes a feeling of lost promise, that the futuristic society the West was promised in the 80s, 90s, and 00s, the sounds, the flying cars, the space exploration, which I remembered the tail end of; never came into fruition, replaced with the demoralising ugliness of Wokeism.

Peter Thiel has made the same point; we live in a disappointing future where technological progress has stagnated.

Whilst the combined intelligence of society has been spent on developing super-addictive, harmful social media platforms and endless bureaucratic regulations, the majority of science fiction from the 20th century imagined the early 21st century as far more technologically advanced, at least in a meaningful, substantive sense, than what we got. To give an example, ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’s’ depiction of human space exploration in 2001 is far more advanced than OTL 2024, where there is a struggle to even return to the Moon, let alone build bases.

Blade Runner is imagined as a dystopian future. That was clearly the intention of Ridley Scott, and he does a good job at presenting the dystopian aspects of the society.

However, whilst it makes the film look far better aesthetically, if we’re doing a political analysis of the kind of society that exists in its world, the film definitely has a ‘night-time and rain bias’.

We never see ATL Los Angeles during a bright summer's day, only when it is at night, raining, sunset, dawn, or very misty. This presents the world in a very dystopian light; which is of course the intention and a good aesthetic choice, but it paints our view of this world in a more negative light than is perhaps justified.

As fans of the film will know, in the original theatrical release, the final scene is Deckard and Rachel driving across a forest, very much showing us ‘another side’ of this world. Mandated by the studio, this scene is very out of place in the context of the aesthetics of the rest of the film, hence why it was removed in the director's cut, as Ridley Scott doesn’t consider the theatrical release as true to his vision.

But what if we really are being shown the world of Blade Runner in the most dystopian light? Perhaps we just see the underworld of a city in dark colours, and nature hasn’t been completely destroyed, like we see in the theatrical release?

There are certain clues throughout the film that suggest this wouldn’t fit, for instance, Rachel says ‘of course it is’ when Deckard asks if the owl is artificial, and Zhora says ‘do you think I’d be working in a place like this if I could afford a real snake?’ However, for the sake of my argument, these could be interpreted differently, Rachel could be saying the owl is ‘of course’ artificial because she works for a genetic engineering/technology company, and Zhora’s line about real snakes being expensive could be because snakes really are expensive.

The Context of 1980s Anglo-Saxon Anxieties

I say ‘Anglo-Celtic’ because even though the film is set in America and is an American film, Ridley Scott himself is British, so no doubt there is a ‘British touch’ to the vision which shouldn’t be discounted. Indeed, Hollywood has always been a cross-Anglo-Celtic enterprise, with British actors and directors always having made their mark, as well as Irishmen, Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders.

Seeing depictions of the present day from science fiction made in previous decades is always fascinating. On the one hand, it’s interesting to see what they got right and what they got wrong. But on the stuff they got wrong, it is also a fascinating insight into WHY they got it wrong. It is a snapshot into the social and political anxieties of that era, and how they compare to our own.

One political concern at this time included mass overpopulation, particularly in Asia. Alarmed by sky-high Chinese birthrates, many Western commentators doubted that the ‘One Child Policy’ was ever going to be enforced. Books like Paul R. Elrich’s 1968 book ‘The Population Bomb’, and the Club of Rome’s 1972 report ‘The Limits to Growth’ assumed high Asian birth rates were here to stay, coming to the terrible conclusion that population growth would outstrip agricultural productivity and cause mass famine.

A related concern to overpopulation was environmental destruction, though the specific issues of focus were different to today, with more focus on pollution by hazardous chemicals than climate change. Acid rain and the destruction of the Ozone layer were examples of environmental challenges in the late-20th century that were later thankfully resolved. Blade Runner is not the only work of science fiction that explores these themes of overpopulation and environmental destruction; another example is the novel ‘Make Room, Make Room’ (1966) and its loosely based film adaptation ‘Soylent Green’ (1973).

On the economic and political front, there was widespread anxiety in America during the 1980s that, due to its breakneck economic growth and superior work ethic, Japan was going to become an economic superpower and overtake the United States. Agreements like the Plaza Accord and Ronald Reagan’s import restrictions of Japanese cars were a desperate attempt to try and secure American domestic industry against superior Japanese products, though it seemed a foregone conclusion that Japan would become a larger economy than the US with a much smaller population.

The Reagan/Thatcher years were a period where corporate power rose and trade union power declined. Wokeism was not something that was a present threat, as it seemed, particularly from the perspective of the liberal, that the 1960s counterculture had in fact been utterly crushed, and its advocates ‘sold out’. There was an increasing acceptance that capitalism was the only game in town, ‘there is no alternative’ (TINA) was the mantra of Thatcher, that would become even more pronounced in the following decade after the collapse of the USSR.

Whilst presenting liberal critiques and anxieties in many respects, the film also presents a ‘Moral Majority’ anxiety around the increasing delinquency and hedonism that characterised youth culture. Prostitution and drug use are seen throughout the film. This was the primary issue the Religious Right had: the very individualistic, pleasure-focused culture that facilitated family breakdown that took off during the 1960s. Such trends have actually very much declined since then, being replaced with a far more sanctimonious, equality-focused, and reality-denying form of cultural leftism.

This is related to the period’s fears about urban decay. New York had not experienced the revival it would go onto have later on in the 1980s, so ATL Los Angeles has similarities with Martin Scorsese’s ‘Taxi Driver’ (1976) in presenting the logical conclusion of decaying urban landscapes and ‘White flight’, with the contemporary economic and social trends assumed to continue.

So all in all, the concerns that a liberal Hollywood filmmaker, aka Ridley Scott, would have in the 1980s about the future, are radically different to our own as Sensible Centrists in the 2020s.

But it is interesting how none of the social anxieties presented in the film came true; almost their opposites did.

The world is not in danger of mass overpopulation, but rather the opposite, mass underpopulation, causing a collapse in the welfare state as the elderly take up an ever greater share of the population.

Lack of housing development, not an excess of it destroying the countryside, has reduced people’s quality of life.

Gentrification, not ghettoization and urban decay, became the key problem of urban centres.

Corporate power did grow, but not in the Fordist, manufacturing-dominated way presented in the film, but instead corporations were captured by ultra-feminised social forces within bureaucracies, management, HR departments, and outside third-parties, to sap vitality from the productive elements of society.

The Positives of the World of Blade Runner

I will discuss the various areas where I believe that the alternate 21st century presented in Blade Runner is better than what these years have ended up being in the West.

Expansionist and Colonialist Spirit

In the world of Blade Runner, humans have developed advanced technology to be able to colonise space, enabling the traditional American frontier spirit and quest for expansion to continue, though we never see these space colonies on-screen.

In a timeline where the development of SpaceX’s Starship is being held back by endless ‘environmental impact assessments’ and legal reviews, Blade Runner’s presentation of such an unapologetic quest of colonisation and extension of homesteading into space seems a vastly superior future.

Genetic engineering is freely used in the world of Blade Runner. This is a vast improvement our timeline, where the advancement of genetic engineering has been repressed by draconian ‘health and safety’ and ethics regulators, created by the emotional cries of parasite activists, who have done so much to stunt the growth of technological progress through endless red tape around ‘ethics’, and conveniently prevent research that might break the hegemony of the Woke worldview.

In the world of Blade Runner, Western men freely embrace their Faustian drive, instead of it being miserably repressed by the Longhouse.

Urban Development and Low Cost of Housing

ATL Los Angeles has vast, magnificent skyscrapers and high-rise buildings. There has been no NIMBY stranglehold on planning development, and the emigration of Whites to off-world colonies has made property very cheap. We can see this with Rick Deckard’s home. He has a spacious apartment which he earns on a single income, even able to retire in middle age before being called back into service whilst still being able to keep his apartment.

YIMBY policies, even when it isn’t public housing and is entirely private sector, are a good thing, as prices will decline as more dwellings are built (though perhaps not as quickly as one would like).

Tokyo, which the ATL Los Angeles is in large part based on, has had an easy and flexible planning system that has stopped the chronic rise in housing costs present in cities of other developed nations. Therefore, despite modern Japan’s many problems, like an ageing population and economic stagnation, housing costs aren’t one of them. To give another example, despite its magnificent skyscrapers and luxury feel, Dubai’s housing is comparatively cheap due to its liberalised planning laws. Whilst Singapore-style state construction of housing is probably the best way to maintain affordable housing, and still is crucial if private developers create a cartel to artificially reduce supply, incentivising private sector development is a good thing in and of itself.

High-rise buildings are a good thing for society. You can house people with less land. This shows why the giant skyscrapers of ATL Los Angeles are a good thing. In addition to liberal, standardised planning laws, perhaps the city has been incentivised to build high-density housing with a high Land Value Tax (LVT), something Estonia has.

Non-Woke, Pro-White Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism has been the target of much hate amongst anti-Wokeists, and justifiably so, as the term in the modern West means anti-White. It should more accurately be described by Eric Kaufmann’s term ‘Asymmetric Multiculturalism’.

However, there are other societies that have made multiculturalism work and large-scale benefit the native population.

For instance, Dubai’s population is majority immigrant, with native Emirate citizens consisting of only around 12% of the population. But far from competing for jobs, the Emiratis have become a ‘master class’. The immigrants are all non-citizens, with no long-term claim to Dubai being their home, and only there to be used as a source of cheap labour, with Dubai’s valuable currency sent home for remittances.

With the entire West suffering from low birthrates, the economic incentives for immigration makes sense, but only if it benefits the native population. Constant concerns about ‘equality’ prevent this and turn it into ethnic-spoil politics.

But a nation like Dubai does not need to worry about birthrates, because it can always rely on the supply of cheap immigrant labour. In fact, lower birthrates may make people better off as there is more wealth-per-person belonging to the native high caste.

The key issues with multiculturalism is that it is incompatible with notions of egalitarianism and democracy. If you make a claim to egalitarianism, non-White groups will constantly cry ‘racism’ for the smallest ‘microaggressions’ and any unequal group outcomes in which Whites perform better. In a democracy they will be able to create ethnic blocs for their interests, like we saw in the Rochdale by-election.

However, a multiculturalism that is meritocratic and authoritarian can work, and indeed, much as it has become a buzzword for the left, there ‘is’ something to be gained from diversity, for instance with food choice.

One famous multicultural society was the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which operated under a monarchic system of government. This system operated quite well, Jews were not mass murdered like they would be in the age of ‘liberal national republics’, because the aristocratic elite had an interest in not murdering their taxpayers, and therefore kept majoritarian ethnic grievances under control (though not due to a true belief in ‘equity’ like the modern West).

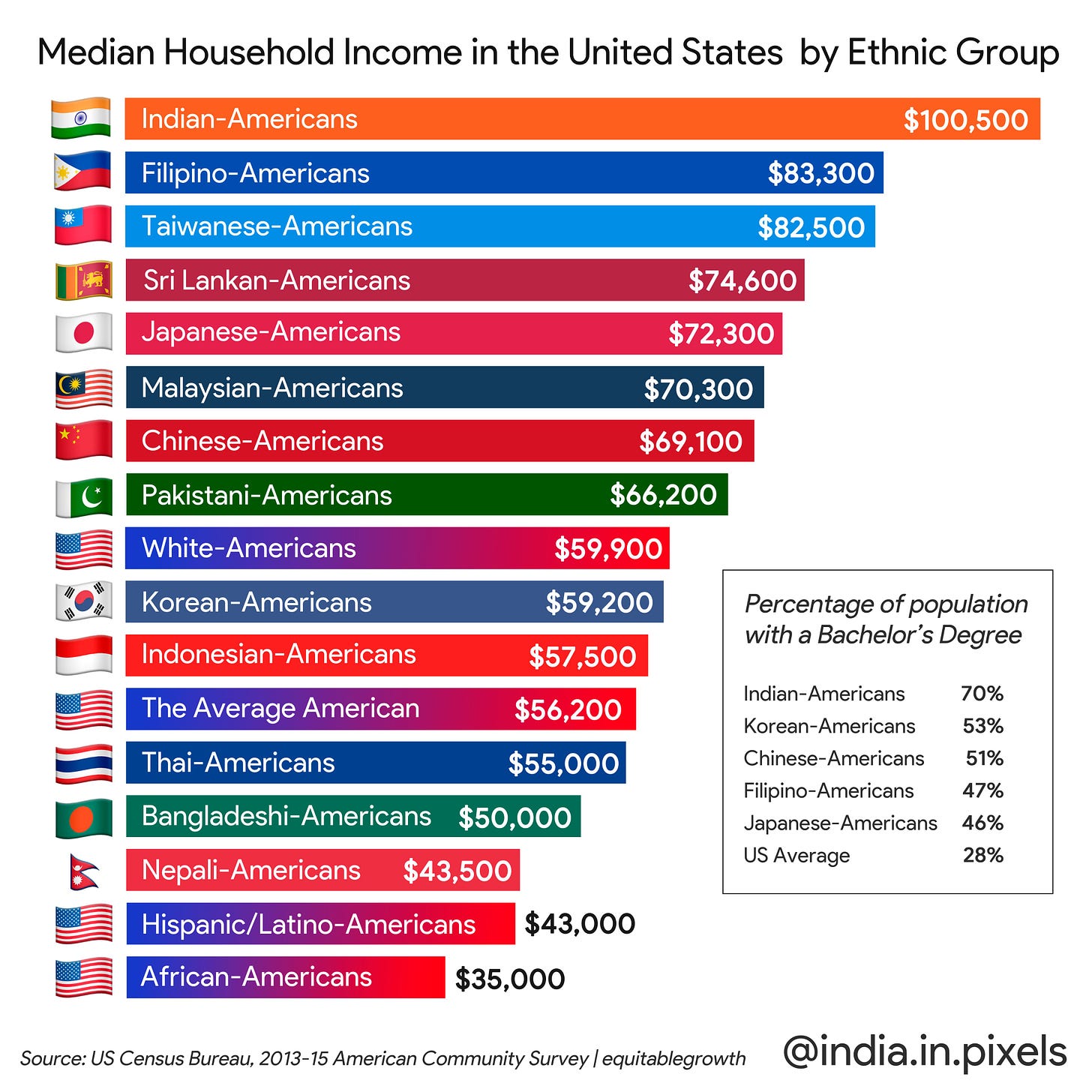

ATL Los Angeles’ immigrant population is composed overwhelmingly of Asians, who tend to be the most law-abiding American citizens, even more than Whites. Asian-Americans, despite their physical distinction from Whites making assimilation more difficult compared to other Whites, have thrived when it comes to contributing to the state and society.

There is only a problem when they are recruited by left-wing activists to hurt White interests and stir up ethnic grievances, for which their physical distinction poses a risk, and is why most Asian Americans still vote Democrat.

However, in an authoritarian state like a monarchy, that is not an issue.

ATL Los Angeles has a more Chinese and South East Asian feel in its underbelly than its elite circles, which seem to be composed mostly of Whites (probably disproportionately Jews) and joined by some Japanese. Naturally gifted individuals, disproportionately from high IQ ethnic groups, are able to utilise their talents to further human progress without barrier, whereas lower IQ groups are on average lower in status, though no doubt some individuals rise to the top ranks, and they accept this, because they don’t have a choice if they want to stay. This is a meritocratic society, what Academic Agent would call the ‘Rufo Reich’, except I see it as an unironically good thing, something I will discuss in a later article.

Japan as a Superpower

In Blade Runner, Japan has fulfilled its promise of superpower status, something that was believed to be around the corner in the 1980s, until the ‘Lost Decades’ and plummeting fertility rates brought that to a halt.

In the world of Blade Runner, it is clear that Japan has outpaced America as the cultural hegemon. The clothes Rachel wears are an interesting mixture between mid-20th century Western female dress and traditional Japanese dress, which suggests that Japanese culture is considered ‘high status’ and something White Westerners are trying to emulate.

In the world of Blade Runner, the late 20th century Japanese continuation of Fordist industrial capitalism and the relatively non-political society, where there is no special role for ‘activism’ or ‘participation’, is not under threat of being eroded by globohomo; it instead has spread to the United States.

Japan’s rise to superpower status in the world of Blade Runner was likely due to having at least replacement-level birthrates, and not being forced to sign the ‘unequal treaty’ of the Plaza Accord, which was correct from an American-interest standpoint, but unfortunate, as civilised Japan’s rise was squandered and American soft power became corrupted by Wokeism.

Other changes like not going into endless debt in the 1990s to protect against job losses may also have helped avoid Japanese decline.

High Birthrates Fuelling Expansion

Far from our own timeline, when there is an aging population sapping the world of its vitality and drive for expansion, the world of Blade Runner assumes that the high Asian birthrates of that time would just continue. This would be a better outcome than today, as the Chinese are a relatively high IQ group, and as stated previously, tend to be law-abiding and successful in the West.

It is difficult to comprehend why people were so concerned about a booming population in the late 20th century, when compared to a shrinking population, a growing population incentivises expansion. Space colonisation would have been a much more practical policy solution to solving overpopulation. However, underpopulation poses a very different set of challenges; the drive towards expansion dissipates, and a declinist mindset takes over the entire society, with elderly voters wanting nations to turn into retirement homes and sapping all productivity. Covid lockdowns were a case of the young being sacrificed to protect the interests of the old, many of whom would have died anyway in a few years and therefore lockdowns only served to thwart the life chances and spirit of the young.

Public vs Private Space

The separation between the public and private space is a general positive feature of the world of Blade Runner. None of this ‘bringing your whole self to work’ which has erased public standards of behaviour. In the ‘public spaces’ of Blade Runner, we see people well-dressed, well-mannered, polite, and civilised. In ‘private spaces’, the seedy underworld of ATL Los Angeles, there is far more decadence and degeneracy, but the key word here is ‘private space’. The public and private spaces benefit from being separated, not sapping the vitality away from each other. The private is far less ‘naughty’ and ‘exciting’ in a world where obese women at the Student Union emphasise the harms of ‘kink-shaming’ and kids are present at gay pride parades with nudity and fetish gear.

The world of Blade Runner is one mass entrepreneurship, with numerous small traders. This suggests that, contrary to presentation, the society isn’t just a corporatocracy, but a place where it is possible for people of numerous backgrounds to thrive without restrictive licencing requirements.

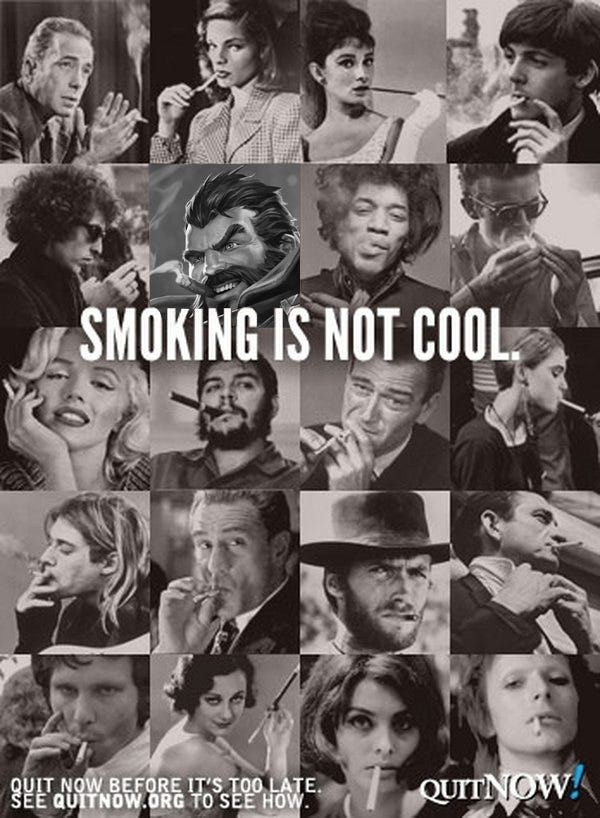

Another key point is the presence of smoking. I hold the anti-smoking lobby in contempt, arguably paving the way for the odious infringement on personal liberty in the name of ‘health and safety’ we see in our modern age. There was a coolness and vitality to smoking, that radiated a sense of a ‘free people’, who were living in the moment and not bogged down by endless scolding about lung cancer, because they correctly argued that we all die in the end, a sentiment sorely lacking during the Covid pandemic.

Wikipedia and establishment media would not have you believe it, but the power of the ‘Tobacco Lobby’ is virtually non-existent, as Rishi Sunak’s complete ban on smoking, phased-in for people born after a certain point, shows you. The power has entirely belonged to moralistic, puritanical anti-smoking activists, not content to let people face consequences for their own actions, for instance through paying for smoking-related healthcare/higher insurance premiums, but wanting a tyrannical ‘nanny state’. It is the same sentiment behind ‘sugar taxes’ in Britain, the same Longhouse activists putting ‘health and safety’ above people’s freedom.

The world of Blade Runner looks like a far more ‘free’ society than ours today. There are no endless regulations and procedures. Small traders can set up shop without draconian licencing requirements, men have easy access to prostitution, people seem able to have the right to bear arms (as Rachel shooting Leo seems to show) and the right to self-defence is far more emphasised than in modern Britain, or even even modern California. They are free from moral scolding from the left, and perfectly represent the spaces outside of strict social oversight that Bronze Age Mindset (1) emphasises are so essential for one’s sense of personal liberty.

The Postliberal critiques of our modern age seem suited to the world of Blade Runner, but they are certainly not the same society that we live in today.

Law and Order alongside Limited Government

It is easy to see the ATL Los Angeles as a lawless society, with decadent behaviour in the underworld.

But is that actually true? Has law and order really completely broken down?

Or is it instead simply a libertarian society, where the state only creates laws it is prepared to enforce, and the laws that do exist are enforced rigorously?

I feel that’s the kind of space that exists in ATL Los Angeles, akin to the below BAP quote:

Just a few weeks ago I was outside night club in city that is still untouched by first-world regimented hygiene: well-lighted, clean streets made safe for women come at a high price for the mood of a city. In this place the government and bureaucracy couldn’t extend its rules and cleanup efforts even if it wanted. There are then many nooks and hidden corners that are under no one’s control. In this no-man’s land there is mafia, so many perverts, there is some crime, but it’s kept at mostly very low or nonviolent level because place is full of off-duty cops on the make and no doubt spooks foreign and domestic, and who knows what else. (Bronze Age Mindset, pp. 14)

As said previously, Asians commit crimes at a lower rate on average than Whites, so the large Asian population in ATL Los Angeles would probably not be responsible for a rise in crime rates.

In addition, the fact that Rick Deckard has orders to ‘kill on site’ any replicant he finds, suggests that the world of Blade Runner is not one that is lawless. When there are serious threats to the public order, it uses lethal force, and does not bother with the endless ‘human rights appeals process’. This inhumanity is indeed part of the story, and is almost certainly unfair in regards to the replicants that are ‘more human than human’, but stepping back from the narrative of Blade Runner and focusing entirely on the setting, whilst the Chinese stalls and markets might give it a third world appearance, there is very little evidence to suggest that crime is actually rampant.

Conclusion

Blade Runner is a beautifully made film. The aesthetics look incredible, the acting and story are both fantastic, and it is a staple of science fiction films. It created the modern cyberpunk genre, and alongside it many other subgenres of past-themed futurism, like Atompunk and Decopunk, which Blade Runner also utilised. The Vaporwave aesthetic is very much harkening back to the science fiction of the 1980s of which Blade Runner is a prominent example.

In some ways, chiefly on the question of the environment, the setting of the film does not look like a nice place to live. However, if we were to take the setting of the film, what limited information we are given about it, away from the central narrative, there are also positives about this society, which are deliberately brushed under due to (great from an aesthetic point of view) only scenes with limited daylight being shown.

Even when dystopian, the setting has utopian elements, the fact that humanity has reclaimed its frontier spirit is something to be admired, as it is the total antithesis to the Woke ideology that taunts us today.

What one might consider a dystopia another person might consider a utopia. The world of Blade Runner is obviously the nightmare of an intersectional Woke leftist, but as I, as a Sensible Centrist, despise their values, their image of ‘dystopia’ would naturally include some things I like.

A techno-commercialist future would have been better than what we got.

Bibliography

Bronze Age Pervert. Bronze Age Mindset. 2018.

LOL - the same question occurred to me. first rate writing!

Excellent piece. I've had a Classics professor show this fim in a mythology class as an example of the influence of Oedipus Rex. I can see now that the revelation of a tragic circumstance is not limited to the characters in the film.